We know a lot about planets that are millions of light-years away, but when it comes to the basement of our own house, it’s a different story. The bottom of the sea remains one of the least explored environments on Earth. While we invest enormous curiosity in what lies beyond our atmosphere, the vast underwater world, right beneath our feet, receives only a fraction of the attention.

And yet, it is there, in this silent, dark, and pressurized frontier, that some of our most complex engineering feats take place. Hidden from sight, thousands of meters below the surface, critical assets operate in conditions far more hostile than outer space: crushing hydrostatic pressure, corrosive saltwater, and zero visibility.

This is where subsea operations live. Before the smallest oil drop ever reaches a FPSO, they first depend on a carefully orchestrated ecosystem of components: Wellheads, Christmas trees, manifolds, umbilicals, subsea control modules, and the robotic eyes and hands that keep everything running: ROVs.

These structures are not just metal anchored to the seabed. They are the foundation of offshore production. Understanding them and ensuring their integrity is what allows the industry to safely extract resources from places humans cannot physically go. Thus, if so much remains unknown about the seabed itself, how do we manage to drill, extract, and transport resources buried thousands of meters below it?

The Anatomy of Subsea Production Systems

The answer begins with the wellhead, the first gateway between geological formations and the surface. This equipment anchors the well to the seabed and provides the structural and pressure integrity necessary for drilling operations to occur safely. Beyond simply acting as a foundation, the wellhead supports casing strings and creates a secure pressure boundary that isolates different underground formations. Without this barrier, the integrity of the entire wellbore would be compromised, turning the seabed into an uncontrolled escape path for hydrocarbons.

Directly above the drilling operation sits the blowout preventer (BOP), a heavy, fail-safe stack of valves and shear devices designed to seal the well in an emergency and prevent uncontrolled flows; its role is literal containment. While its importance is often only remembered during crises, the BOP is constantly monitoring well pressure, ready to shear drill pipe if necessary, and close off the wellbore

Once drilling moves to production, the Christmas tree is installed on top of the wellhead: a compact, multi-valved assembly that controls flow, routes production, and delivers the functional controls operators use to manage the well. It regulates the flow of hydrocarbons, functioning as the subsea equivalent of an operational heart. Its reliability determines whether the system can handle sudden changes in pressure or flow without catastrophic consequences.

Further out, manifolds serve as the central coordination points of subsea production. They receive fluids from individual wells and channel them into the broader subsea network, allowing operators to manage multiple production streams. More than simple connectors, manifolds incorporate valves, sensors, and control modules that regulate pressure, direct flow paths, and isolate sections of the system when maintenance or intervention is required. By doing so, they transform a collection of independent wells into a unified, controllable subsea system, ensuring that production can be balanced, optimized, and safely routed to processing facilities.

To sustain all these systems, umbilicals stretch from the surface down to the seabed, carrying the lifelines of modern offshore operations: power, chemicals, communications, and hydraulic control. These flexible, multi-layered cables are engineered to withstand marine currents, abrasion, and years of movement without losing integrity. They are, in essence, the nervous system of subsea infrastructure: every valve movement, pressure reading, and injected chemical dose depends on them.

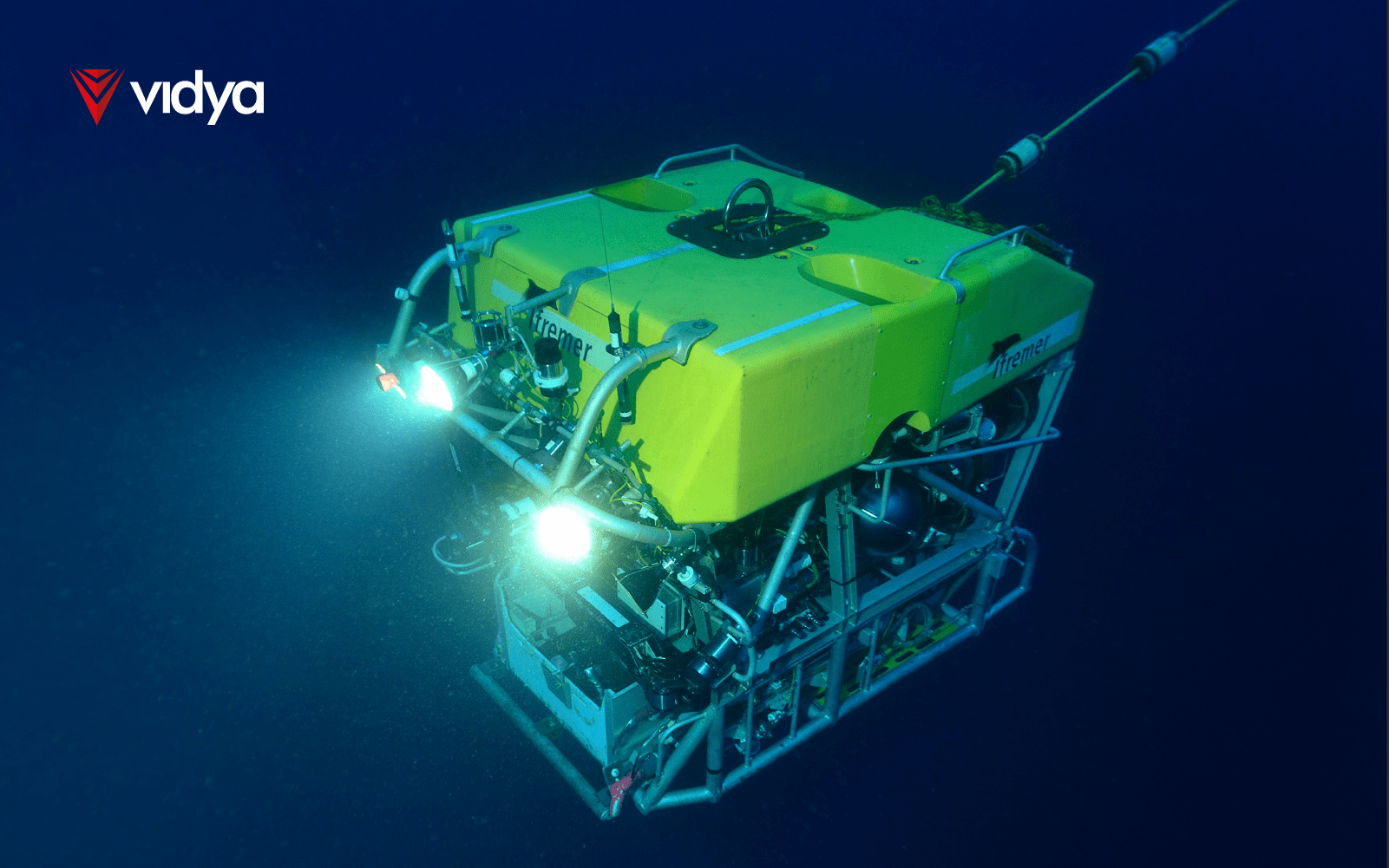

None of this, however, would function without a presence capable of seeing and acting where humans cannot. That role falls to Remotely Operated Vehicles (ROVs), which navigate darkness, pressure, and cold to perform inspections, interventions, and repairs in places no diver could survive.

Challenges of Operating Subsea Systems

Operating subsea systems isn’t merely about building strong hardware; it means managing a complex, remote underwater network under constant strain. Because these assets lie kilometers beneath the surface, every inspection, repair, or maintenance job requires specialized vessels, remote-operated tools, and detailed planning. Each operation carries high costs and often long delays. For this reason, the challenges of operating subsea systems extend far beyond engineering; they begin the moment humans must interact with an environment we cannot physically enter.

Environmental

The first and most unforgiving of these is pressure. At depths that can exceed thousands of meters, every square centimeter of equipment faces crushing loads that would deform or rupture anything not engineered to perfection. This constant hydrostatic pressure is not a variable that peaks and fades; it is ever-present, waiting for the smallest design flaw or material weakness to turn into catastrophic failure.

Compounding this is the corrosive nature of seawater. Unlike terrestrial environments, where corrosion can be managed through coatings and inspections, subsea systems endure continuous exposure to salt, oxygen, and microbial agents that aggressively attack metals. Even with advanced alloys, cathodic protection, and chemical inhibitors, corrosion remains a silent adversary, steadily eating structures and reducing the lifespan of components designed to operate for decades. It is not simply a maintenance issue; it is a constant engineering constraint that defines what is possible underwater.

Then there is the challenge of darkness. Sunlight fades quickly beneath the ocean’s surface, and at operational depths, visibility drops to zero. Systems must therefore rely on artificial illumination and sensors to navigate, inspect, and interact with infrastructure. Darkness represents a barrier that complicates every human attempt to understand and monitor these assets. It turns simple tasks into complex technical operations and makes real-time perception dependent on technology that must function flawlessly under extreme conditions.

Operational

However, environmental constraints are only half the story. The operational challenges of subsea systems introduce an entirely different level of complexity. Unlike topside assets, where engineers can physically walk up and observe a valve or flange, inspecting these structures is not a routine visual check but a coordinated campaign that requires remotely operated vehicles (ROVs), specialized vessels, and highly trained technicians. A 2020 Society of Petroleum Engineers report shows that upkeep of subsea wells demands substantial resources: operators worldwide spend over US $500 million annually on subsea-well inspection alone.

Maintenance follows the same logic: nothing can be repaired directly by human hands. Every intervention (whether replacing a component, adjusting a valve, or cleaning marine growth) requires specialized tooling, perfect planning, and heavy resource mobilization, further inflating the costs associated. For this reason, the use of ROVs and deepwater support vessels is the rule for subsea interventions. Indeed, according to a 2023 Market Growth report, globally, there are ~3,000–3,500 ROVs deployed in offshore oil/gas operations.

These remotely operated vehicles serve as the only practical “hands and eyes” humans have at seabed depth. When an integrity inspection or a maintenance call-out is required, an ROV is deployed from a support vessel, maneuvering through complex underwater terrain to inspect valves, measure wall thickness, check for leaks, or operate subsea controls. The same Market Growth report stated that an ROV requires ~$1.2 M maintenance per year.

That dependence on remote equipment introduces another deep vulnerability: nearly all intervention below water depends on the availability, condition, and performance of ROVs. In these conditions, due to subsea equipment being remote and harshly exposed, maintenance cannot always wait for ideal conditions. According to a 2022 article by Iheanyichukwu, operators often postpone non-critical maintenance because “the cost and logistics outweigh the urgency,” but doing so increases long-term risk of degradation, leaks, or more serious failures.

How Technology Is Rewriting Subsea Integrity Management

If operating subsea assets means fighting pressure, corrosion, darkness, and logistical constraints, then managing their integrity has traditionally been a slow and fragmented effort. Data is scattered across systems, inspections rely on ROV footage that takes hours to review, and teams struggle to build a clear picture of what is happening at the seabed. In other words, the difficulty isn’t only in the environment; it’s in the information itself. And this is where technology begins to change the equation.

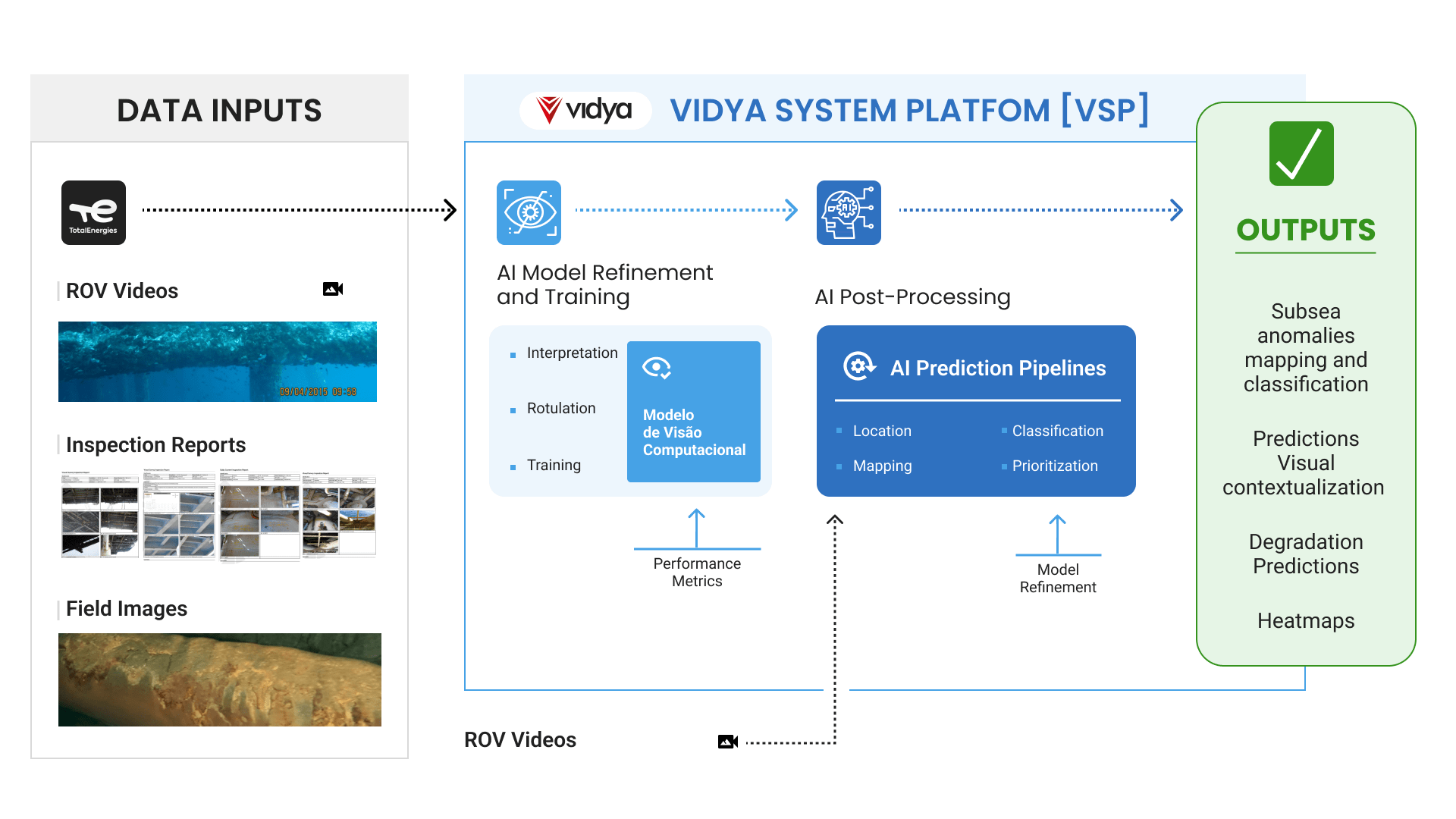

Vidya Technology, an international company specialized in Asset Integrity Management for large-process industries, designed the Digital Well Integrity application to bring order to a landscape defined by fragmentation. Instead of treating pressure logs, leakage tests, ROV videos, 360° imagery, engineering documents, procedures, and operational records as isolated pieces, the platform consolidates them in one structured environment. Existing engineering, IT, and OT datasets are ingested, processed, and contextualized into a 3D representation of the subsea asset, turning what used to be scattered information into a coherent digitalized subsea layout.

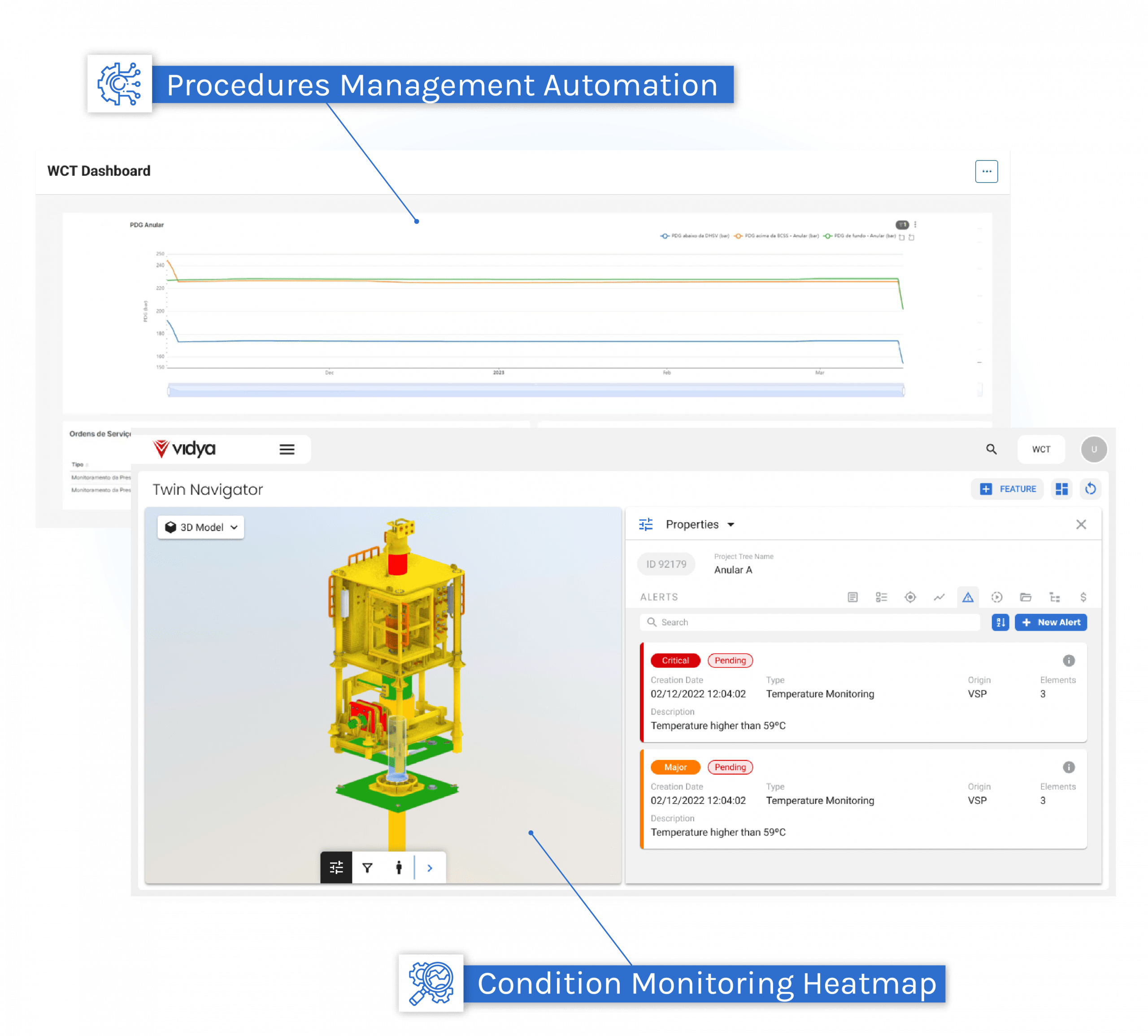

In these conditions, the platform integrates what traditionally required manual checks and cross-verification. Leakage test monitoring, pressure behavior, periodic procedures, and operational rules are parameterized directly into the system, enabling the system’s triggering of alerts and the visualization of abnormal conditions inside the 3D environment. Instead of reviewing multiple spreadsheets, logs, and systems, integrity managers see deviations emerge dynamically, linked both to the event and its physical location.

This digital workflow reduces the friction that normally delays subsea decision-making. Work orders, procedural steps, and activity history are organized chronologically and tied to the asset’s structure, which simplifies planning and increases traceability. The result is not speed for its own sake, but clarity: the right information, in the right context, without the long retrieval times that often slow integrity teams.

Thus, by processing ROV images and videos through AI computer vision, the system also strengthens one of the weakest points in subsea work, interpreting visual data consistently and quickly. Anomalies detected in footage are classified, mapped with their coordinates, and displayed on dashboards and heatmaps. In practice, this integrated workflow gives operators what the subsea environment rarely offers: visibility. In a setting where pressure, corrosion, and logistics already impose enough challenges, the ability to manage integrity with structure and situational awareness becomes a strategic advantage rather than a luxury.

Conclusion

The subsea world will always challenge the limits of engineering, logistics, and human exploration. But the industry is no longer navigating this environment blindly. By combining engineering expertise with digital tools capable of organizing, contextualizing, and interpreting vast amounts of information, operators can shift from reactive routines to structured, confident decision-making. The goal is not to simplify the seabed (it never will be), but to give teams the clarity needed to operate safely in a place where visibility has always been scarce. In a world obsessed with exploring the cosmos, mastering the depths beneath us may be one of our most complex missions.

![Image of a woman using Vidya System Platforms [VSP] on a tablet.](https://vidyatec.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/1-capa-blog-CS@2x-1024x640.png)