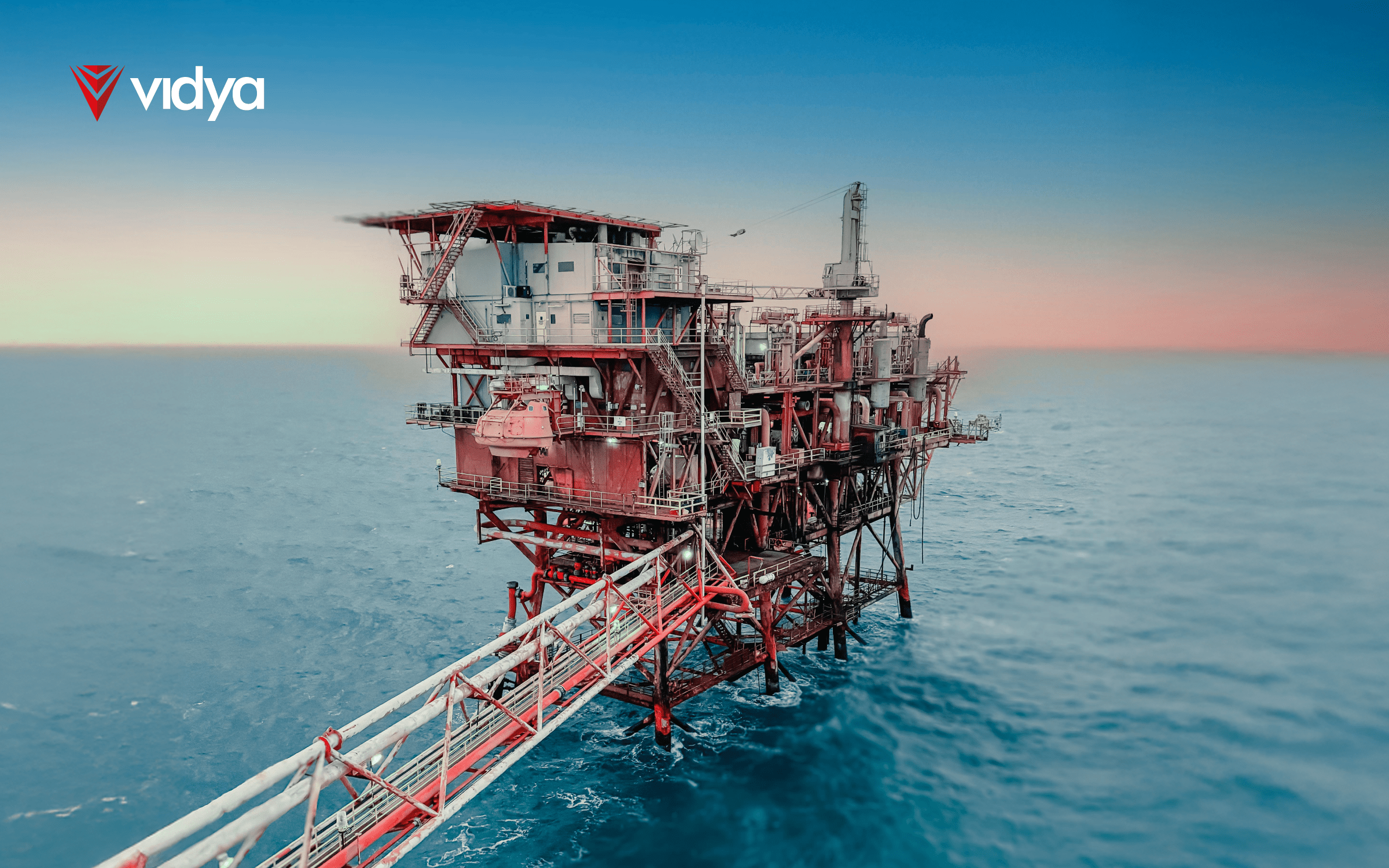

Decommissioning is the set of technical, environmental, and regulatory activities required to safely retire offshore oil and gas assets at the end of their productive life. It represents the definitive closure of operations and involves well plugging and abandonment, removal or repurposing of topsides and substructures, and the remediation of the seabed. More than a single engineering task, decommissioning is a multidisciplinary process that integrates offshore engineering, subsea operations, environmental science, logistics, and regulatory compliance.

International conventions such as OSPAR, along with national regulatory frameworks and environmental legislation, establish strict requirements for how offshore assets must be retired. As a result, decommissioning demands the same level of technical rigor and planning as field development and production phases.

Why Offshore Assets Must Be Decommissioned

Offshore oil and gas installations are designed for finite operational lifespans. As fields mature, the degradation of structures becomes unavoidable. Corrosion, fatigue, marine growth, and long-term exposure to harsh offshore environments progressively reduce structural reliability and increase operational risk. Over time, the probability of failures, hydrocarbon leaks, and safety incidents rises significantly.

Decommissioning addresses these risks by permanently eliminating sources of environmental contamination and safety hazards. It also ensures compliance with legal obligations imposed on operators and governments, while reducing long-term liabilities associated with inactive infrastructure. In addition, the removal of obsolete assets frees seabed areas for alternative uses, including new offshore developments, shipping routes, and renewable energy projects. In mature offshore basins, decommissioning is no longer an exception but an inevitable and strategic phase of asset lifecycle management.

Obsolete Assets as the Trigger for Decommissioning

At the core of every decommissioning project lies the concept of asset obsolescence. An obsolete asset is any installation, system, or piece of equipment that has lost its ability to generate technical, economic, or operational value. This condition may develop gradually through aging and degradation or be accelerated by regulatory changes, market dynamics, or technological evolution.

In offshore and maritime environments, obsolescence is particularly critical due to strict safety and environmental requirements. Assets approaching or exceeding their design life often demand disproportionate maintenance effort while presenting elevated operational risk. Once an asset becomes technically unreliable, economically unjustifiable, or non-compliant with regulations, decommissioning becomes the most responsible and sustainable option.

Technical and Operational Challenges

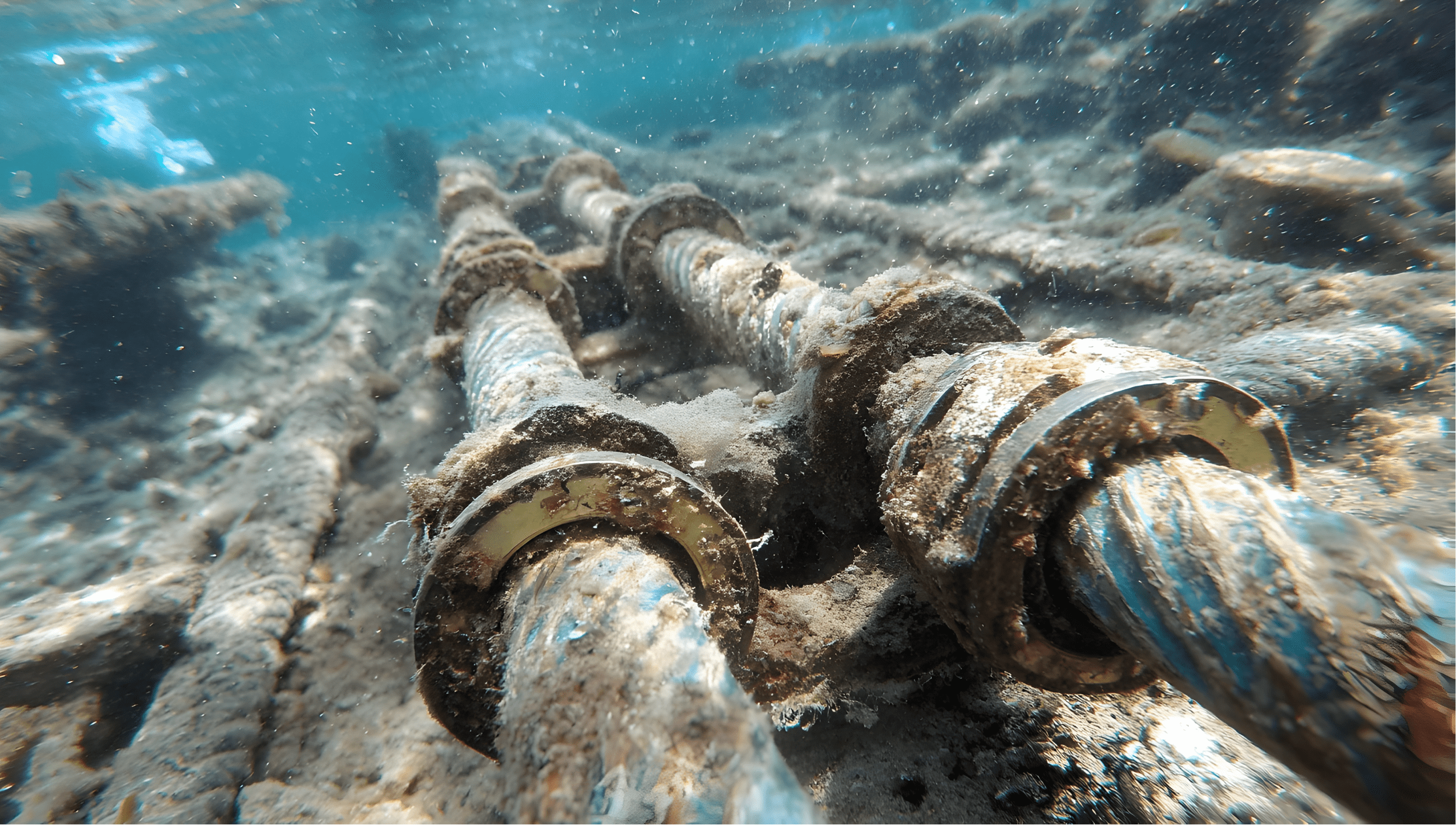

Decommissioning is widely recognized as one of the most complex and capital-intensive phases of an offshore project. Structural degradation accumulated over decades complicates lifting, cutting, and removal activities, particularly when original design data is incomplete or no longer representative of actual asset conditions. Marine growth and corrosion add uncertainty to load calculations and structural behavior during removal.

Data quality is another critical challenge. Many offshore assets were designed and installed before digital asset management became standard practice, resulting in fragmented or outdated documentation. This uncertainty directly impacts engineering decisions, risk assessments, and execution strategies.

Well plugging and abandonment present additional complexity, especially in mature fields where wells may suffer from compromised integrity, casing corrosion, or unknown downhole conditions. These factors often require advanced abandonment techniques, specialized equipment, and extended offshore campaigns.

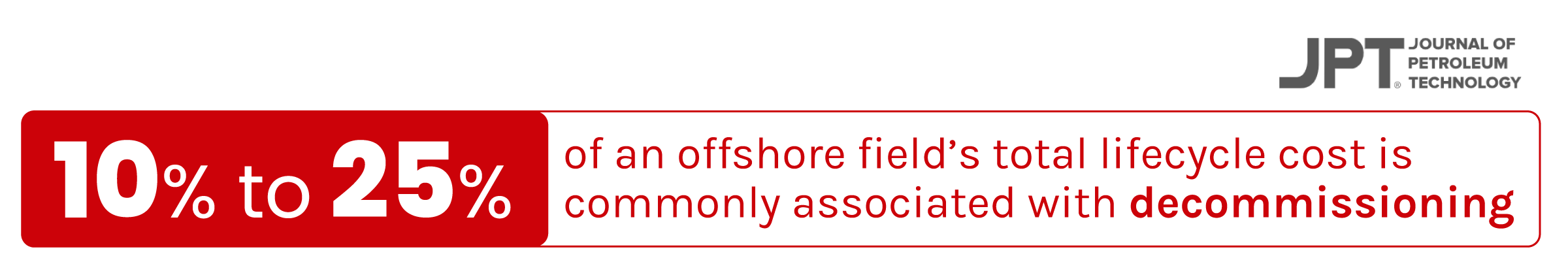

Environmental constraints further increase project complexity. Decommissioning activities must account for sensitive marine ecosystems, contaminated sediments, and strict waste management requirements. At the same time, offshore logistics, heavy-lift operations, subsea interventions, and adverse weather conditions elevate safety risks and cost exposure. It is not uncommon for decommissioning costs to represent between 10% and 25% of the total lifecycle cost of an offshore field.

How Decommissioning Projects Are Executed

Despite their complexity, decommissioning projects typically follow a structured and phased execution model, often delivered through short- to medium-duration offshore campaigns. The process begins with detailed engineering and planning, supported by structural, subsea, and environmental surveys. These studies define removal strategies, risk mitigation measures, and regulatory pathways.

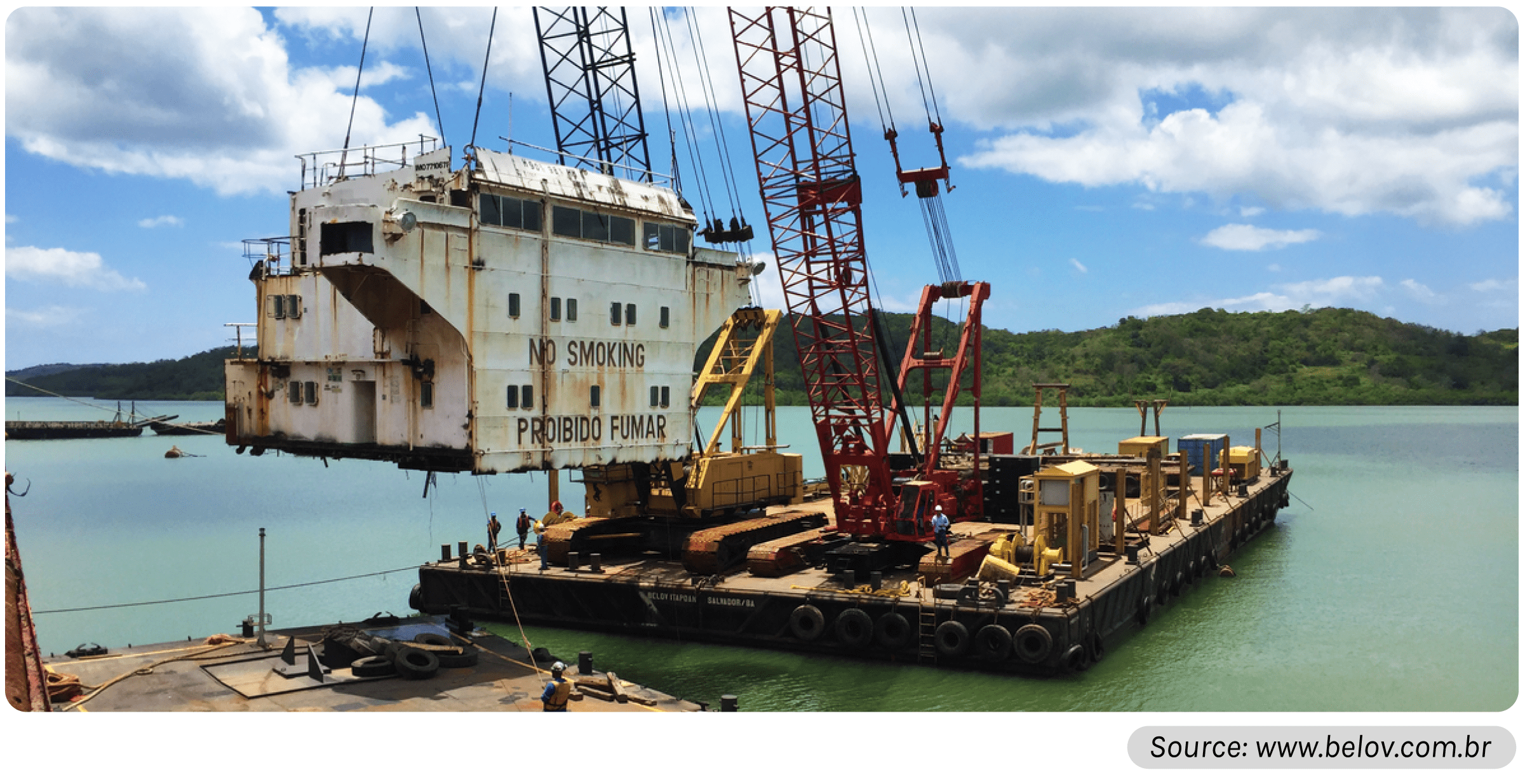

Once planning is complete, wells are permanently plugged and abandoned using combinations of mechanical barriers and cement plugs to ensure long-term isolation. Hydrocarbon inventories are removed, and topsides are cleaned and rendered hydrocarbon-free. Removal of topsides is then performed using heavy-lift vessels or modular dismantling techniques, depending on asset size and local constraints.

Substructures such as jackets or gravity-based structures may be fully removed, partially removed, or left in place when regulatory frameworks allow. The final phase involves seabed clearance, debris removal, and post-decommissioning environmental monitoring to confirm that the site is left in a safe and compliant condition.

From Asset Removal to the Recycling Value Chain

Decommissioning does not end with the physical removal of offshore structures. Instead, it activates a complex recycling and reuse ecosystem that extends across multiple industries. Platforms, FPSOs, and vessels entering decommissioning initiate flows of materials, waste, logistics, regulatory oversight, and economic activity.

Recycling facilities play a central role in this process by performing controlled dismantling and material segregation. Steel, which represents the majority of structural mass in offshore assets, is recovered and reintegrated into the steelmaking industry. This practice is increasingly aligned with a broader trend in steel production, where recycled feedstock has become a strategic input rather than a secondary resource. According to company disclosures from leading steelmakers, up to 71% of steel production already relies on recycled material (well above the global average), significantly reducing demand for virgin raw materials and lowering the carbon footprint associated with primary steel production.

Beyond steel, a wide range of components can be refurbished, reused, or sold into secondary markets. Pumps, valves, electrical systems, auxiliary equipment, and industrial furnishings often retain significant residual value, transforming decommissioning from a purely cost-driven activity into a potential source of revenue.

Environmental Responsibility, Logistics, and Regulation

One of the most critical aspects of the recycling chain is the management of hazardous materials. Residual hydrocarbons, heavy-metal coatings, asbestos, and contaminated chemicals require strict handling, transportation, and disposal procedures. Compliance with environmental and occupational safety regulations is essential to prevent ecological damage and reputational risk.

The logistics required to support decommissioning and recycling are equally significant. Port infrastructure, towing and pilotage services, transportation of materials, and waste handling operations generate measurable economic impact in coastal and industrial regions. This is particularly relevant in countries like Brazil, where large numbers of offshore assets are approaching the end of their productive life, creating substantial medium-term decommissioning opportunities. Brazil currently has more than 160 platforms in operation, a significant portion of which have exceeded 25 years of useful life. Approximately 13 units are scheduled for removal by 2028, with dozens more slated for decommissioning in the following decade, indicating a growing demand for decommissioning and recycling services for materials such as steel.

Decommissioning, Decarbonization, and Value Creation

As the energy transition accelerates, decommissioning has become closely linked to decarbonization strategies. Steel recycling contributes directly to emissions reduction and aligns with the emerging concept of green steel. At the same time, structured decommissioning programs support safer oceans, reduced environmental liabilities, and more sustainable industrial practices.

Rather than being viewed solely as a financial burden, decommissioning is increasingly recognized as a strategic discipline, particularly in mature offshore provinces in Brazil. The scale of planned activity underscores this shift: investments related to offshore platform decommissioning in the country are estimated at approximately R$ 64.4 billion through 2028, driven by an aging asset base in which 53 production units have already exceeded 25 years of operation.

Petrobras alone has announced US$ 11 billion in decommissioning investments over the next five years, with around 70% allocated to well plugging and abandonment activities and 30% dedicated to subsea equipment removal, including flexible lines. When supported by data, technology, and integrated planning, decommissioning enables operators to manage risk, ensure regulatory compliance, stimulate industrial value chains, and extract residual value from aging offshore assets, transforming an end-of-life obligation into a structured, value-oriented process.

The Role of Technology in Modern Decommissioning

Technological advancement has become a key enabler of safer and more efficient decommissioning. Specialized cutting tools, remotely operated vehicles, and advanced lifting solutions have significantly reduced offshore exposure and execution risk. Digital engineering models and integrity data platforms improve planning accuracy and allow operators to better anticipate structural behavior during removal.

Major offshore contractors have demonstrated how integrated vessel fleets, subsea equipment, and digital workflows can be applied to complex decommissioning scenarios. Real-world applications show that innovation is no longer optional but essential for managing the growing global decommissioning backlog.

Conclusion

Decommissioning represents the final and often most challenging chapter in the lifecycle of offshore oil and gas assets. It sits at the intersection of engineering, environmental stewardship, regulation, and industrial sustainability. Organizations that approach decommissioning proactively and strategically will be better equipped to navigate the technical complexity, control costs, and contribute positively to the evolving offshore energy landscape.