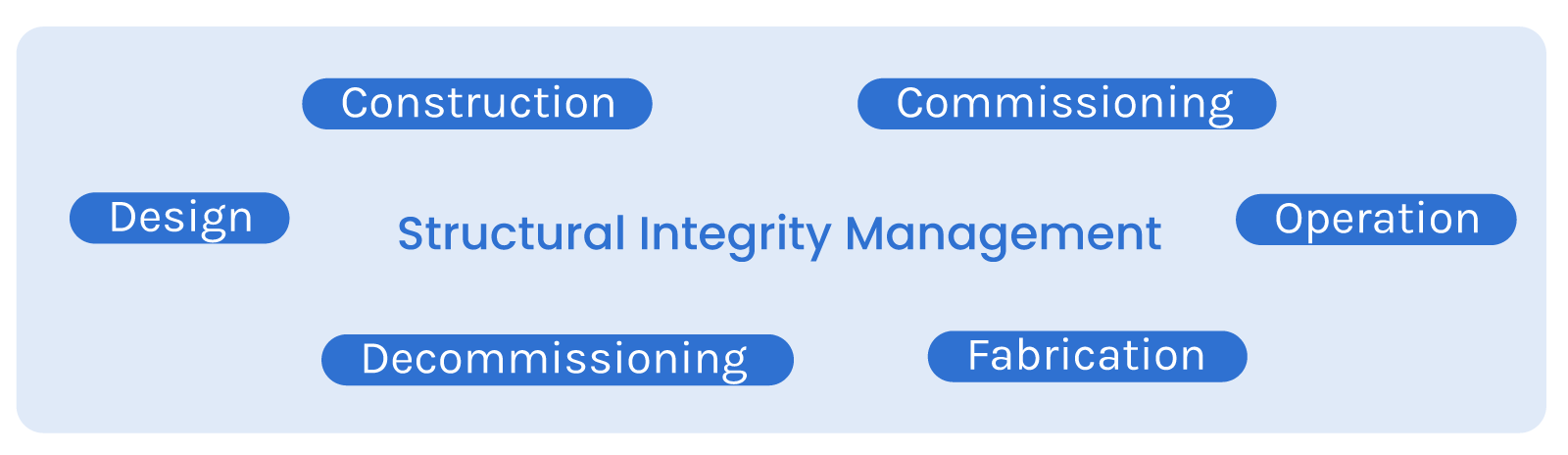

Structural Integrity Management (SIM) refers to the systematic process of ensuring that a physical asset, whether a pipeline, offshore platform, storage tank, bridge, or structural frame, retains sufficient strength, stiffness, and safety margins over its intended life, under both normal and extreme loads, environmental degradation, and operational changes. It is not just a one-off check; instead, Structural Integrity Management spans all phases of an asset’s life: design, fabrication, construction, commissioning, operation, and decommissioning.

In essence, structural integrity combines inspection, monitoring, modeling, assessment, and maintenance planning to detect, evaluate, mitigate, or prevent structural damage, fatigue, corrosion, defects, or other forms of deterioration before they escalate into failures or unsafe conditions.

Common Causes of Structural Failures

Structural failures in industrial assets are typically the result of a combination of design deficiencies, material degradation, and operational stress. Among the most common causes are corrosion, fatigue cracking, and overloading, often intensified by harsh environmental conditions such as waves, wind, and temperature fluctuations.

Poor maintenance practices, inadequate inspection routines, and deviations from design specifications can further accelerate damage or leave it undetected until a critical point. Human error, whether during construction, operation, or decommissioning, also plays a significant role in weakening structures over time. Ultimately, most failures are preventable; they stem not from unforeseen events, but from gradual deterioration and overlooked warning signs in structural integrity management.

Why is Structural Integrity Management so important in heavy-asset industries?

Many industrial sectors depend on large capital infrastructure whose failure can incur high safety, environmental, and financial consequences. For example, in oil & gas, a structural failure, say in a platform leg or pipeline support, can cause hydrocarbon release, environmental damage, catastrophic downtime, or even loss of life.

In mining, structural elements such as tailings dams, hoists, conveyor supports, and structural frames are subjected to heavy loading, abrasion, fatigue cycles, and must be reliably safe.

In energy and power (e.g. wind towers, substations, hydro plants), structural elements face dynamic loads, harsh environments, and regulatory scrutiny. Infrastructure, petrochemicals, maritime, bridges, rail, and aerospace all rely heavily on accurate integrity management.

In many sectors, failure to manage structural integrity costs much more than the preventive investment. For instance, in Oil & Gas, downtime costs have escalated. An ABB survey stated that many industrial operations incur unplanned outages costing about USD 125,000 per hour.

Over a year, 32 hours of unexpected downtime per month (384 hours annually) would equate to nearly USD 48 million lost per facility (and that estimate may be outdated, as rates have reportedly doubled).

In the context of structural failures, according to the OCI group, a steel-framed industrial facility under construction suffered a collapse during construction caused by insufficient temporary bracing (wire ropes were severely undersized). Loss was estimated to be over US$1 million.

Another incident that demonstrates the importance of efficient structural integrity management took place during a decommissioning operation, where part of an offshore jacket structure (a leg and skirt pile weighing around 27 tonnes) suddenly gave way due to severe corrosion, leading to a fatal accident.

The incident highlights how structural integrity challenges persist even during dismantling phases, emphasizing the need for continuous management throughout an asset’s entire lifecycle.

These numbers illustrate the scale of risk and the demand for conscious, proactive integrity management. Yet in practice, many organizations struggle with the fragmentation of data, delayed decision cycles, or blind spots in their integrity programs.

Thus, structural integrity management is more than an engineering discipline: it is a strategic enabler of safe, reliable, and cost-efficient operations in any sector that depends on structural assets.

Challenges and Bottlenecks in Structural Integrity Management

While the theory and methodology are well established, real-world implementation of structural integrity management often faces significant challenges. Understanding these bottlenecks is essential for articulating how digitalization and integrated systems can enhance efficiency and accuracy

- First, data fragmentation and lack of integration are pervasive problems. Inspection reports, thickness measurements, corrosion probe data, design drawings, sensor logs, MOC (Management of Change) records, maintenance records, and even personnel notes are often stored in different systems or silos. Reconciling them is time-consuming and error-prone.

- Second, data quality, completeness, and traceability pose a challenge: missing metadata, inconsistent formats, errors in recording, or gaps in historical records limit the usefulness of aggregated datasets. Many integrity decisions are only as good as the underlying data.

- Third, inspection resource constraints are real. There is often a limited number of qualified inspectors, access constraints (e.g. remote, offshore, confined spaces), cost pressures, and safety risks. Optimizing how, where, and when to inspect is a complex trade-off.

- Fourth, aging assets and legacy complexity introduce uncertainty. Structures built decades ago may lack full as-built records or suffer from undocumented modifications, unknown residual stresses, or material degradation not foreseen during design.

- Fifth, the interpretation and qualification of anomalies demand high expertise. Differentiating benign defects from critical flaws often requires experienced engineers and advanced modeling; misinterpretation can either lead to excessive conservatism (over-repair) or underestimation (unexpected failure).

- Sixth, cost-benefit trade-offs and economic pressure: organizations must balance inspection and repair costs with production demands. Sometimes, risk reduction investments compete with other capital priorities, and under tight budgets, integrity programs get deferred.

- Seventh, changing operating conditions (e.g. increased loads, modified duty cycles, new process requirements) may drive structural stresses beyond original design bases. Without re-analysis, integrity plans may lag behind real exposure.

- Eighth, regulatory and compliance complexity: many sectors are subject to stringent safety, environmental, and code/regulation requirements. Integrity decisions must often be defensible to regulators and audited, adding overhead.

- Ninth, skilled workforce scarcity. The rise of digital tools notwithstanding, many organizations struggle to attract or retain engineers with deep structural integrity expertise, especially in interpreting advanced analytics or AI outputs.

- Finally, latency in decision cycles is problematic: from inspection to data upload to engineering evaluation to action, delays may cause risk windows or slow interventions.

Because of these challenges, many organizations remain semi-reactive or partially blind in their integrity management, especially for complex or aging assets.

How Structural Integrity Issues Are Identified: From Symptoms to Diagnosis

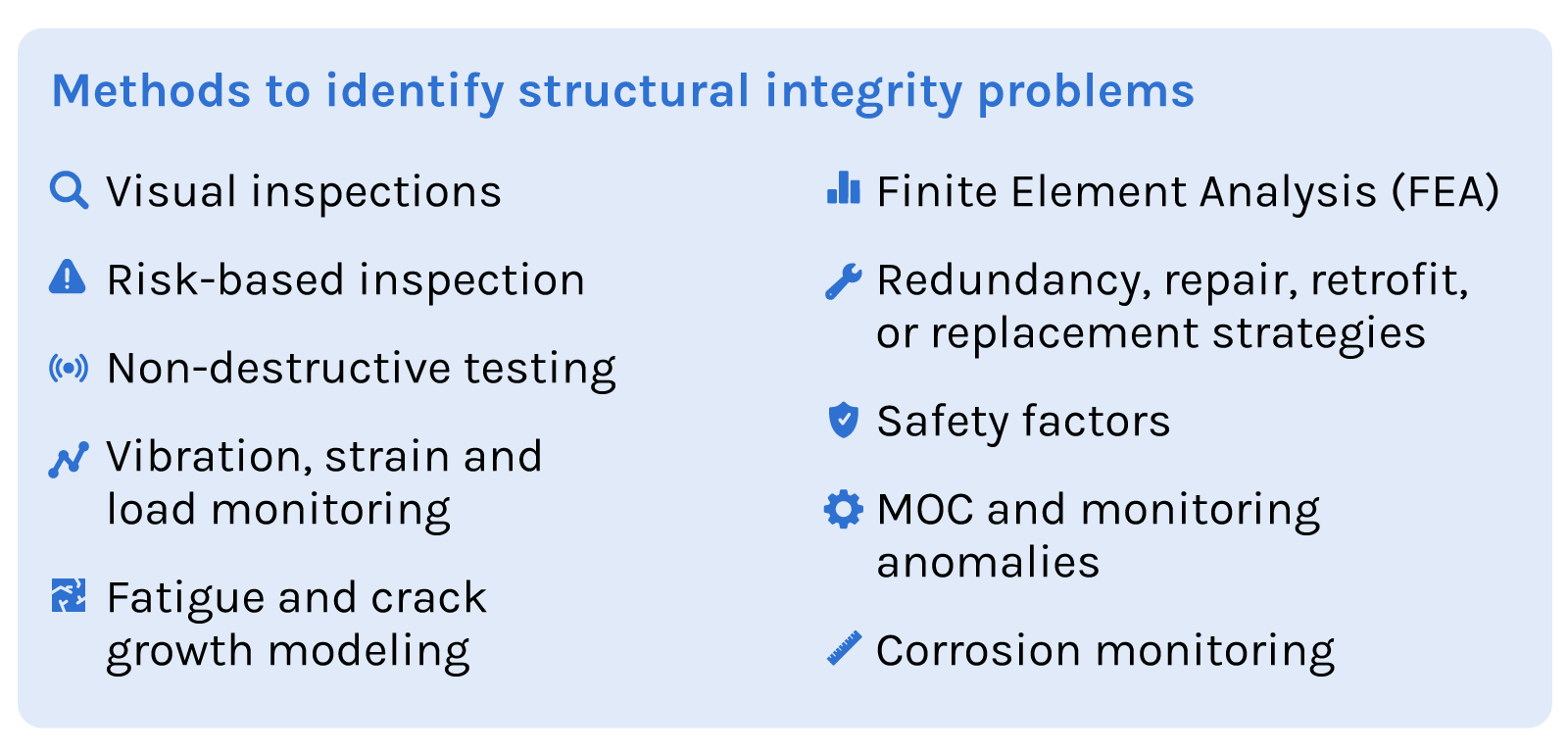

Engineers use a mix of inspection, monitoring, analysis, and diagnostics to identify structural integrity problems before failures occur.

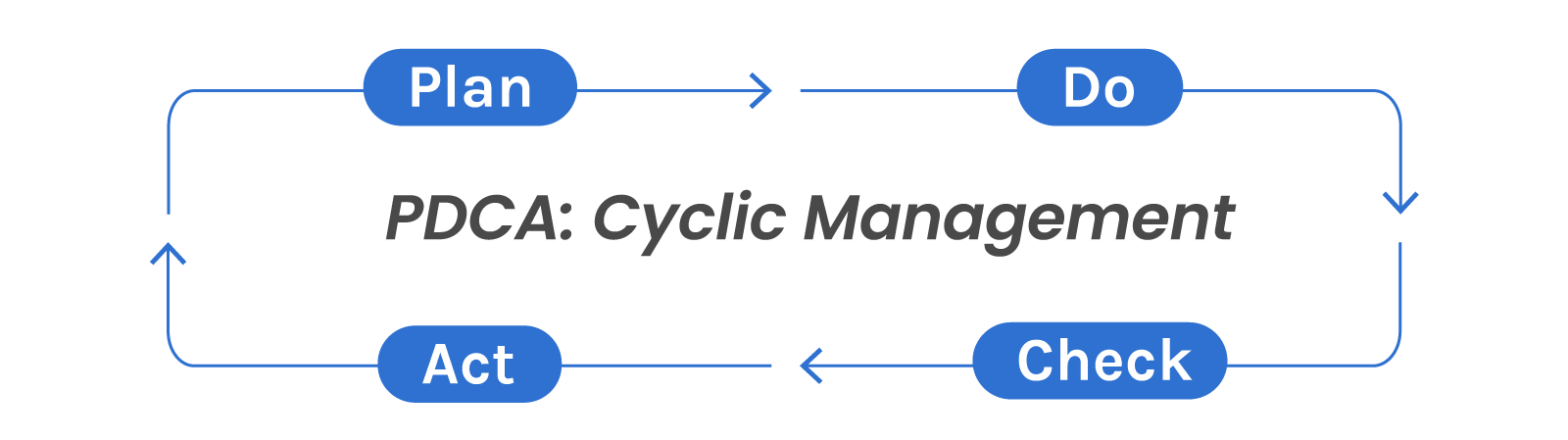

Identifying structural integrity issues is not a one-time activity but a continuous cycle that follows the PDCA (Plan–Do–Check–Act) principle, the foundation of modern integrity management. Engineers apply this cycle to ensure that every inspection, finding, and corrective action contributes to ongoing improvement in asset safety and reliability.

In the “Plan” phase, engineers define integrity objectives, identify critical components, and develop inspection and monitoring strategies based on risk assessments and operational context. This includes setting inspection intervals, selecting appropriate techniques, and determining acceptance criteria according to the asset’s design limits and service conditions.

The “Do” phase puts these strategies into action. Monitoring systems are deployed, inspection campaigns are carried out, and data is collected from sensors, NDT techniques, and field observations. This is where the planned activities are executed, producing the raw information needed to evaluate asset condition.

The “Check” phase involves interpreting and validating that data through analysis, diagnostics, and modeling to assess whether the structure is performing within its design and safety margins. Findings from monitoring, inspection, and analysis reveal potential degradation or deviations from expected behavior.

Finally, the “Act” phase transforms these insights into actions: repairs, design modifications, operational adjustments, or updated inspection plans. The lessons learned are then reintegrated into the next planning cycle, creating a continuous feedback loop that strengthens long-term structural integrity. The process guided by PDCA cycles typically involves:

Visual inspections

These are the first line of defense. Trained inspectors visually examine welded joints, bolted connections, surfaces, coating condition, weld cracks, deformation, corrosion, pitting, cracking, distortion, or loose attachments.

Risk-based inspection (RBI)

Inspection plans are prioritized based on risk (probability × consequence). Areas with elevated risk or those historically problematic receive more attention for mitigating or preventive actions. These methods help focus limited inspection resources on the most critical components.

Non-destructive testing (NDT)

These techniques form the first layer of inspection, allowing early detection of flaws without compromising the asset’s integrity. Techniques such as ultrasonic testing (UT), radiography (X-ray / gamma), magnetic particle inspection (MPI), dye-penetrant testing (DPT), eddy current testing (ECT), acoustic emission, and phased-array ultrasound allow subsurface flaw detection, crack depth measurement, material thickness evaluation, and other internal defect detection.

Corrosion monitoring and thickness measurement

These methods help track material degradation over time, enabling proactive maintenance before failures occur. Regular thickness gauging at preselected “corrosion circuits” reveals metal loss trends over time. Corrosion coupons, probes, and electrical monitoring may be deployed. Data may flag high corrosion rates or unexpected thinning.

Vibration, strain, and load monitoring

These techniques ensure that structures operate safely under dynamic conditions and within design limits. Strain gauges, fiber-optic sensors, accelerometers, or displacement sensors monitor dynamic loads, stress cycles, deflections, buckling tendencies, fatigue stresses, or resonance. These sensors can detect anomalous overshoots, cyclic loading exceeding design expectations, or fatigue accumulation.

Fatigue and crack growth modeling

When small cracks are detected, engineers use fracture mechanics and fatigue life models to predict crack growth, residual life, and to decide on repair or replacement. By comparing measured stress cycles versus design fatigue capacity, remaining life can be estimated.

Finite Element Analysis (FEA)

For more complex structures, large displacement and non-linear FEA analyses can assess stress redistribution, buckling, plasticity, stability under unusual loads, or damage scenarios. Engineers may reconstruct “as-built” models incorporating damage, residual stresses, and geometry deviations to evaluate structural safety and recommend mitigation.

Redundancy, repair, retrofit, or replacement strategies

If modeling or inspection shows degradation, engineers plan interventions. Localized repairs (weld overlays, patching), structural reinforcements, part replacement, or full refurbishment. Sometimes, design modifications or strengthening are applied midlife.

Safety factors, reserve margins, and conservative design rules

Even with active management, designs often include safety factors or overdesign margins to absorb uncertainties in loads, material variability, or unanticipated conditions.

Crucially, these techniques work best when integrated. Inspection findings feed modeling, monitoring refines prediction, and repair decisions inform new inspection plans. In isolation, any single technique risks blind spots or inefficient resource use.

Management of Change (MOC) and monitoring anomalies

Whenever operating conditions change (pressure, temperature, flow, loads) or modifications are made to the system, structural integrity must be re-evaluated. Deviations in operational data, sensor alarms, or unexpected parameter shifts often trigger an integrity review.

In practice, combining these methods yields a more robust detection regime: visual cues can prompt NDT, which yields quantitative data that feed modeling or FEA, which in turn help plan repairs or further inspection.

One common challenge is that many detected defects are subtle or in “blind spots”. Also, damage mechanisms may interact (for example, corrosion accelerating fatigue crack initiation). Aging assets, evolving load conditions, and unanticipated environmental stressors often introduce complexities not captured in the original design.

Lifecycle integrity management

In practice, all the activities described, from design verification to inspections and degradation monitoring, are integral parts of a comprehensive Structural Integrity Management process. When properly executed, integrity management becomes the foundation for effective maintenance planning, guiding decisions on redundancy, retrofitting, and repair strategies throughout the asset’s lifecycle. By maintaining accurate integrity models and continuously feeding operational insights back into planning, engineers ensure that maintenance actions are not only reactive but strategically driven by real structural conditions. In this way, Structural Integrity Management evolves beyond compliance, it becomes the central framework that supports asset reliability, safety, and long-term performance.

Digital twins for Structural Integrity Management

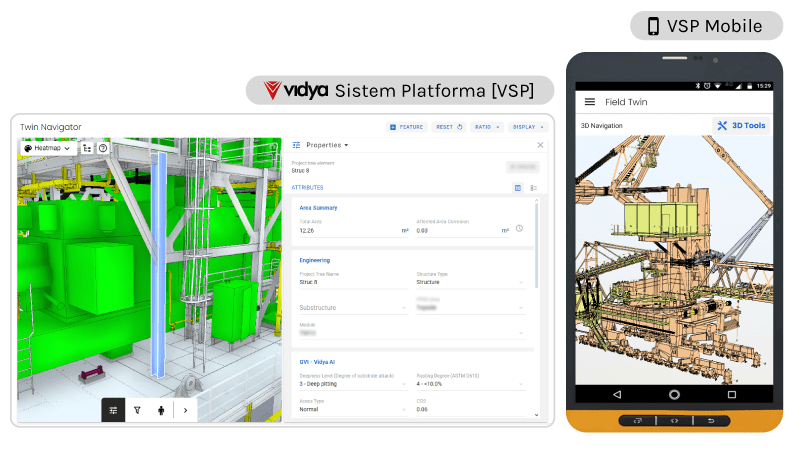

Advanced integrity programs increasingly rely on digital twin technology, virtual replicas that integrate design information, inspection results, sensor readings, and analytical models to represent the accurate condition of assets. Beyond visualization, the core value of a digital twin lies in its ability to orchestrate data flows across disciplines, standardize integrity information, and connect work packages from inspection planning to maintenance execution. By centralizing structural data and operational conditions into a unified platform, engineers can streamline the entire Asset Integrity Management workflow, ensuring that every analysis, diagnosis, and decision is supported by consistent, up-to-date information. This digital backbone enables predictive analysis, improves traceability, and enhances collaboration among engineering, maintenance, and operations teams, transforming integrity management from a reactive activity into a proactive, data-driven process.

Bridging to Digital and Integrated Asset Integrity Management

The importance and presented challenges of structural integrity management make a compelling case for more integrated, digitalized, and data-driven approaches through digital twins. That is precisely where Vidya’s structural integrity solutions come into play.

By integrating large volumes of asset characteristic data (e.g. weight controls, tags, attributes, design specs, fabrication records, installation logs) with structured workflows that capture condition data (inspection findings, corrosion monitoring, SMR (Structural Modification Report), MOC (Management of Change), a digital integrity suite enables more efficient, accurate, and timely decision-making. The system can highlight anomalies, forecast critical thresholds, optimize inspection schedules, and propose repair or reinforcement interventions in a prioritized, risk‐based manner

In this approach, inspection, non-destructive testing, and analysis workflows are recorded via a mobile app. This ensures that field data is captured, contextualized, and associated directly with the relevant asset and location, thereby avoiding transcription errors and data silos.

Such accuracy in data feeds is fed into digital twins, supporting large displacement and staged Finite Element Analysis (FEA) with linear and non-linear material and geometry modeling. Engineers no longer rely solely on spreadsheet summaries or isolated reports; they can operate on a unified model that reflects as-is conditions, damage states, sensor inputs, and design intent.

The digital platform becomes the nerve center of structural integrity management, reducing latency, improving traceability, and enabling more proactive strategies.

Furthermore, advanced analytics or AI can flag potential new damage zones before they escalate, guide predictive or prescriptive maintenance, and help optimize the allocation of inspection resources.

Thus, the traditional challenges such as data fragmentation, inspection latency, decision lag, interpretive complexity, and budget constraints are mitigated. The digital integrity layer transforms raw data into actionable insight, enabling scalable, auditable, and more confident structural integrity programs.

In the context of Vidya’s value proposition, the structural integrity module is part of a broader Asset Integrity Suite, seamlessly linking field workflows, inspection data, material analysis, FEA models, and decision support, creating a feedback loop where every new data point refines the integrity model and helps optimize future inspections and interventions.