The evolution of safety in offshore oil and gas operations is closely tied to global advancements in safety culture, legislation, and best practices. A major turning point in offshore safety history was the shift from prescriptive, equipment-focused laws to performance-based and self-regulatory frameworks that emphasize systemic risk management, asset integrity, and human factors.

From Frameworks to Function: Why Process Safety Became Central

As offshore operations grew in complexity, the limitations of traditional safety models became clear. Regulatory evolution set the stage, but it was the industry’s increasing awareness of systemic vulnerabilities that pushed for a deeper, more technical layer of control.

This is where Process Safety emerged, not just as a regulatory requirement, but as a strategic response to operational risk. Beyond structural soundness and asset availability, companies began to ask: Are our systems truly resilient under abnormal conditions?

To answer that, they turned to a new operational discipline, one that could anticipate failure modes, enforce critical safeguards, and ensure human, environmental, and equipment safety even during worst-case scenarios.

Understanding Process Safety and Its Role in Offshore Operations

At the core of this industry-wide transformation is Process Safety (PSM), a discipline focused on preventing major accidents such as fires, explosions, toxic releases, and catastrophic equipment failures. Unlike occupational safety, which deals with slips, trips, and personal injuries, process safety addresses the integrity of operations involving hazardous substances and complex systems under high pressure and temperature.

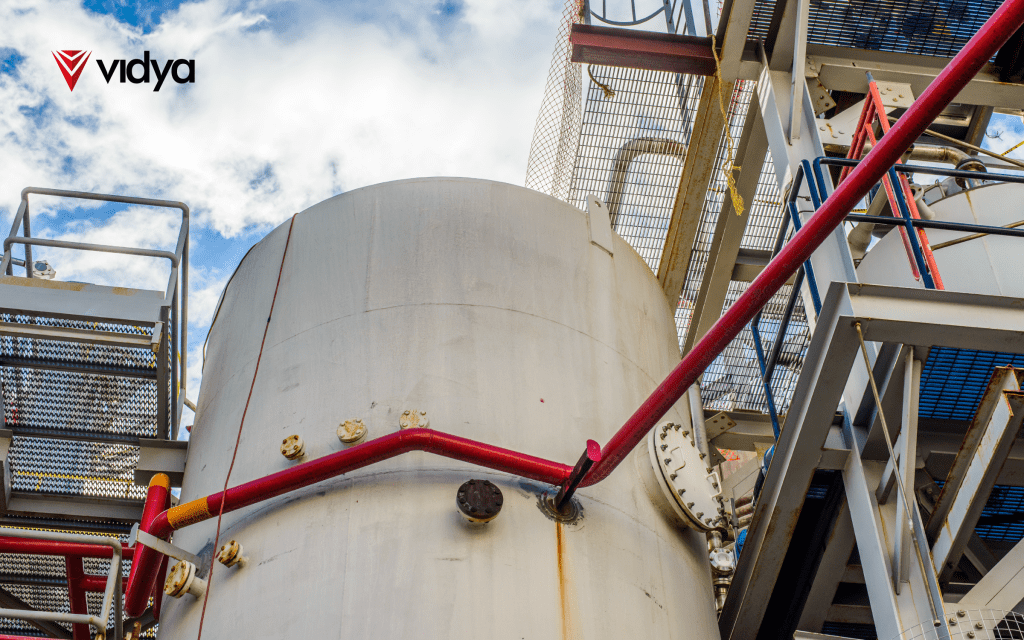

![Process Safety [PSM] prevents](https://vidyatec.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/2-Development-of-Offshore.png)

PSM focuses on ensuring operational controls and systems function reliably and predictably, even under stress. Typically, safety regulations focus on the safety, health, and welfare of workers in factory environments. These prescriptive regulations governed the registration and inspection of machinery, operator competence, and specifications of equipment such as pressure vessels and hoisting machines. However, such regulations did not adequately address the complex operational, environmental, and process safety risks inherent in offshore oil and gas operations.

Over time, broader occupational safety laws were enacted to overcome the limitations of the earlier frameworks. These newer acts introduced self-regulatory mechanisms, requiring the establishment of safety committees, the employment of safety officers, the execution of chemical risk assessments, industrial hygiene monitoring, and medical surveillance. While these reforms marked progress, many national frameworks still lacked specific provisions [1] addressing offshore safety, particularly related to process safety and asset integrity.

This legislative gap has led many offshore oil and gas operators to adopt international standards, such as those from the American Petroleum Institute (API) and the International Organization for Standardization (ISO). In countries with national oil companies or dominant industry regulators, internal control frameworks are also implemented to enforce minimum safety and performance requirements for contractors and partners.

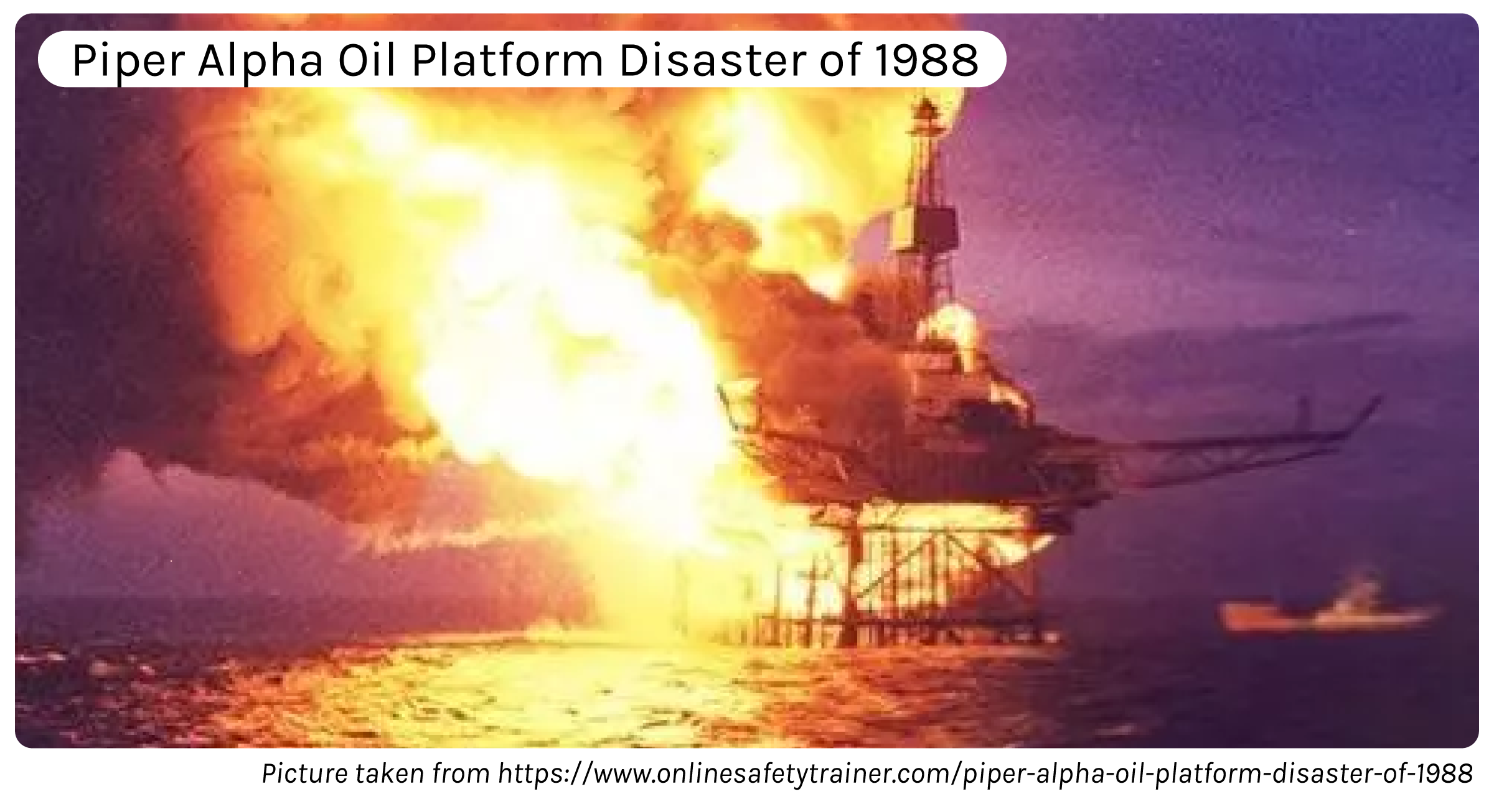

Globally, offshore safety has been shaped by significant incidents. For example, the Piper Alpha disaster (1988) prompted widespread regulatory reform in the UK, including the introduction of the Offshore Safety Act and Safety Case Regulations. In Australia, the Offshore Petroleum (Safety) Regulations introduced stringent safety case requirements. Following the Deepwater Horizon explosion (2010), the United States established the Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE) to strengthen offshore oversight. These developments reflect a broader industry movement toward barrier-based risk management, safety cases, and process safety integration.

Where Asset Integrity Management fits in

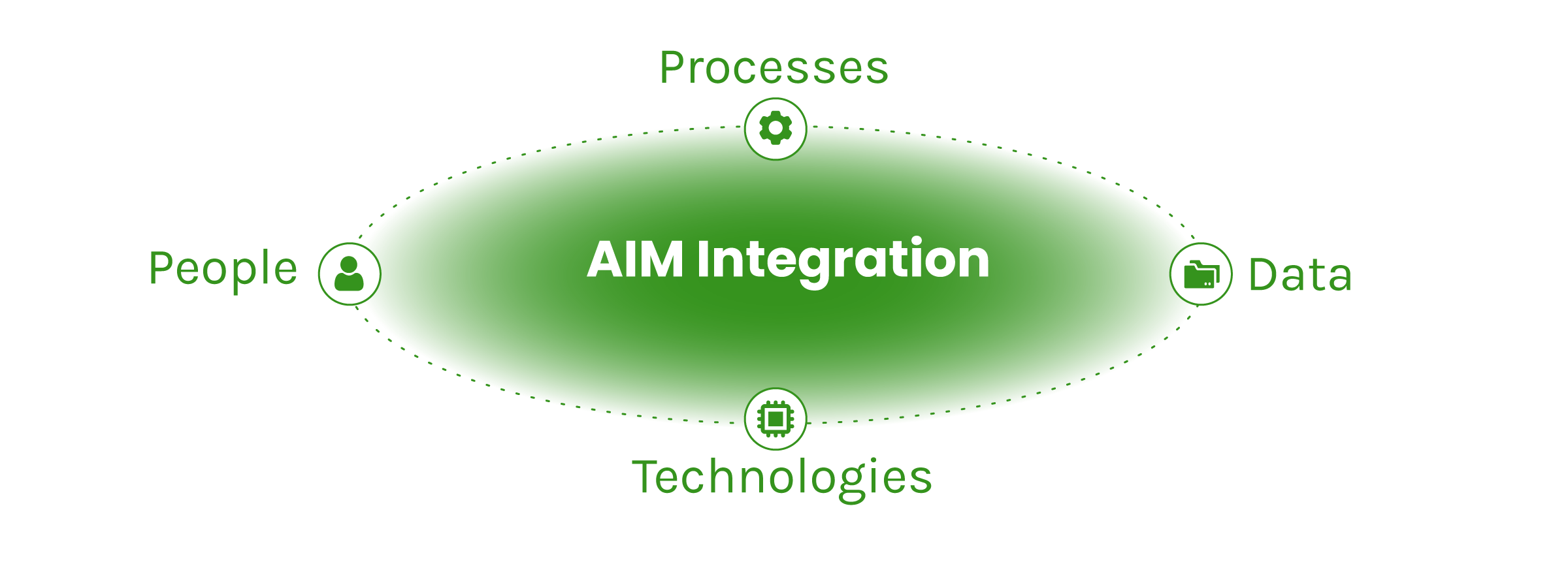

Asset Integrity Management (AIM) is a cornerstone of process safety, reliability, and performance in offshore and large-process industries. Originally rooted in broader infrastructure and utility management practices, AIM evolved within the oil and gas sector into a mission-critical discipline driven by the need for safer, more sustainable, and failure-resistant operations.

Today, AIM is a multidisciplinary and systematic approach that integrates people, processes, technologies, and data to ensure that industrial assets perform their intended function safely and efficiently throughout their lifecycle. It moves beyond compliance to become a strategic enabler of risk mitigation, cost optimization, and operational excellence.

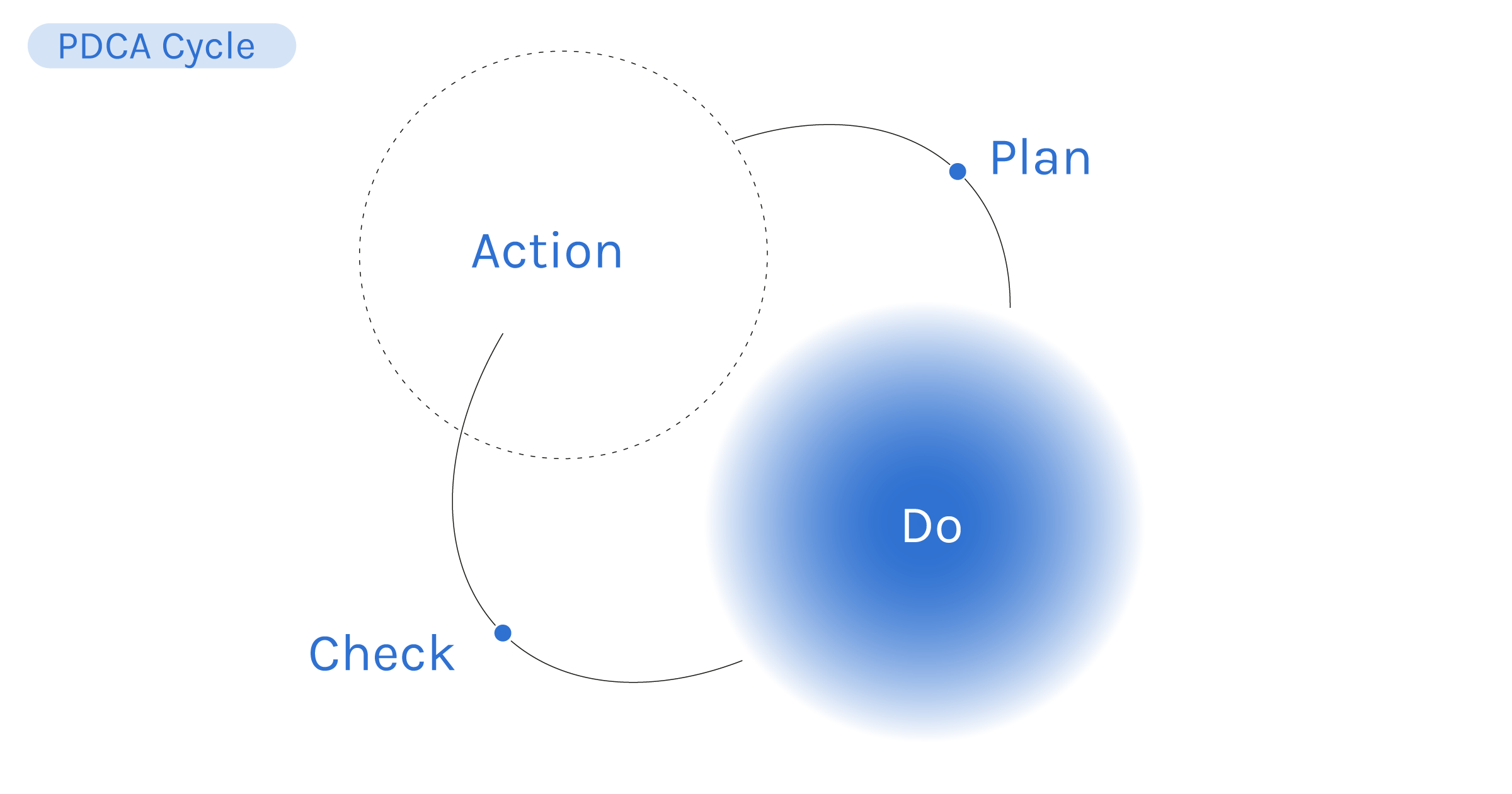

AIM frameworks typically align with the Plan-Do-Check-Act (PDCA) methodology, promoting continuous improvement through each asset phase, from design to decommissioning. Organizations plan by setting integrity objectives based on historical risk and performance data. Execution is carried out via inspection and maintenance programs. Results are monitored through performance indicators, and strategic adjustments are made to close gaps and raise safety and efficiency standards.

AIM and the PDCA Cycle

Furthermore, Modern AIM programs are guided by the principles of continuous improvement, most commonly structured around the Plan–Do–Check–Act (PDCA) framework:

- Plan: AIM establishes asset management policies and long-term strategies, informed by inspection records, risk assessments, and failure data.

- Do: These strategies are implemented through field execution—inspection, maintenance, and testing procedures.

- Check: Data is systematically analyzed, KPIs are monitored, and deviations from expected performance are identified.

- Act: Lessons learned are incorporated back into the system by updating policies, refining procedures, and investing in new tools and capabilities.

This cyclic structure ensures AIM remains adaptive, forward-looking, and performance-driven, especially in dynamic operational environments like offshore oil and gas.

Understanding the responsibilities of Process Safety

Process Safety Management (PSM) is a comprehensive framework designed to prevent catastrophic events such as fires, explosions, and toxic releases in high-risk industrial environments. It focuses on managing operating systems and processes through engineering, organizational controls, and structured risk assessment.

Within this broader safety system, PSM programs implemented by leading oil and gas operators typically align with globally recognized standards, such as the OSHA 3132 (U.S. Process Safety Management of Highly Hazardous Chemicals). These frameworks incorporate core elements, including:

1. Process Safety Information

This is the foundation of any robust process safety program. Operators must maintain accurate, up-to-date documentation of hazardous chemicals, equipment specifications, process flow diagrams, safety data sheets, and operating limits. Access to this information enables informed decision-making, facilitates hazard identification, and supports compliance with global safety standards. Today, digital platforms allow this data to be centralized and accessed in real-time by multidisciplinary teams, improving coordination across departments.

2. Process Hazard Analysis (PHA)

PHA is a systematic approach to identifying potential risks associated with processes and equipment. Techniques such as HAZID, HAZOP, FMEA, and Bowtie analysis are used to map out the causes and consequences of failure scenarios. Leading companies integrate PHA early in the design phase and revalidate regularly throughout the asset lifecycle. When combined with digital twins and real-time data feeds, PHA becomes a dynamic tool for ongoing risk management rather than a static report.

3. Operating Procedures and Employee Training

Clear, standardized operating procedures are essential for minimizing human error. These documents define safe work practices, emergency protocols, startup/shutdown procedures, and maintenance routines. However, documentation alone is not enough. High-performing operators invest in immersive employee training, often using simulations, VR environments, or digital workflows, to build operational discipline and ensure competence at all levels.

4. Mechanical Integrity and Pre-startup Safety Reviews

Mechanical integrity programs focus on the reliability and safe function of critical equipment such as pressure vessels, relief systems, pumps, and piping. These programs include routine inspections, testing, predictive maintenance, and failure analysis. Before any system is brought online, Pre-startup Safety Reviews (PSSRs) verify that construction is complete, all safety systems are in place, and operators are trained, helping prevent startup-related incidents that could compromise both personnel and infrastructure.

5. Management of Change (MOC)

Even minor changes in process conditions, personnel, or equipment can introduce significant risks. MOC protocols ensure that all changes are formally reviewed, documented, and approved before implementation. This includes updating process safety information, retraining staff, and performing new hazard analyses when necessary. Digital MOC tools streamline approvals, track dependencies, and improve traceability across the organization.

6. Incident Investigation

When an incident or near-miss occurs, structured investigations are carried out to identify root causes, contributing factors, and systemic gaps. These findings drive corrective and preventive actions, not only at the local site but across the enterprise. Forward-thinking organizations use incident data to generate leading indicators, identify recurring patterns, and strengthen their safety culture through learning and accountability.

7. Emergency Planning and Response

Effective emergency preparedness is an important element of process safety. This includes developing and practicing response plans for scenarios such as fires, chemical releases, or blowouts. Plans must be aligned with risk assessments and include coordination with local authorities, environmental agencies, and emergency responders. Modern solutions enhance preparedness by modeling response times, resource availability, and possible impact zones using spatial computing and predictive analytics.

A Process Safety Culture

Developing and implementing a robust culture of Process Safety requires more than establishing technical controls; it demands strong leadership, clear accountability, and consistent organizational commitment. Process Safety emphasizes the human and cultural dimensions that sustain safe operations, recognizing that systems are only as reliable as the people and behaviors supporting them. Offshore operators increasingly rely on a mix of performance indicators, both leading (proactive measures) and lagging (reactive metrics), to assess the effectiveness of their safety programs. However, data alone is not enough. A recurring theme among organizations with successful safety outcomes is the visible and continuous engagement of leadership. This includes not only enforcing policies and procedures but actively modeling safety-first behaviors, empowering employees to speak up, and embedding safety as a core value at every organizational level. Ultimately, a resilient Process Safety culture is one where every individual, from frontline workers to executives, understands their role in preventing major incidents and is equipped and motivated to act accordingly.

Conclusion

The evolution of offshore safety management has transitioned from narrow, equipment-focused regulations to holistic systems that integrate asset integrity, process safety, and human performance. While national legislation may vary in scope and detail, many offshore oil and gas operators compensate through adherence to international best practices, robust internal control frameworks, and continuous improvement cycles.

Global experiences shaped by major industrial accidents and the lessons learned underscore the need for barrier-based safety systems, effective risk analysis methodologies, and organizational alignment. As offshore operations grow more complex, the ability to manage integrity and process safety throughout the asset lifecycle remains a critical enabler of safe, sustainable, and efficient performance.